During 1857 and 1858, Napoleon III carefully prepared his new policy to support the unification of Italy. He faced a curious dilemma. He sought to pass himself off as an outstanding Catholic who nevertheless could not fail to recognize the just aspirations of Italian revolutionaries and the errors of the Holy See in the matter.

Earlier articles showed how Napoleon III completely demoralized Montalembert as a champion of the Catholic cause. Nor was he able to replace the Univers with a new paper supported by so-called governmental Catholics. Nonetheless, the latter experience made Napoleon hope that he could revive Gallicanism, the seventeenth-century French teaching that the King’s power exceeded that of the Pope. Resurrecting this historic and popular error would suit Napoleon’s purposes well. To this end, he exploited religious sentimentality while giving great prominence to any fact, however insignificant, that could discredit the Holy See.

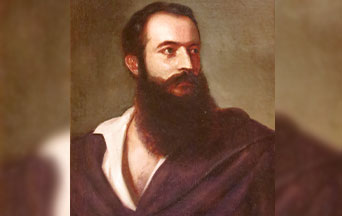

On January 14, 1858, an Italian revolutionary, Felice Orsini, led a plot to kill the Emperor. When the carriage carrying Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie arrived at the opera house on the Rue Peletier for a gala performance, the conspirators set off three bombs that killed eight people and wounded 156. The imperial couple suffered nothing serious, but Orsini’s bombs admirably served Louis Napoleon’s political goals.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

Napoleon III’s near escape made him a hero to his people. As a precaution, the Chamber of Deputies passed a series of security laws that turned the Empire into a police state. At the same time, the French secular press presented the would-be assassin sympathetically as a doomed Italian patriot. Even the Emperor expressed compassion for Orsini.

The bombing also strained relations with Great Britain. The fact that the conspirators had been to England and an English gunsmith had constructed the bombs inflamed French public opinion. It served as a pretext to shake up the Anglo-French alliance. French suspicions were further increased by the well-known fact that England opposed the unification of the Italian Peninsula.

Finally, the Emperor made a trip to Brittany, to which he carefully gave a highly religious slant. The Catholics saw it as a pilgrimage to St. Anne of Auray in thanksgiving for the failure of the Orsini attack. Napoleon III and the Empress prayed at the famous shrine, accompanied by an emotional crowd. The Emperor’s speeches during the trip were designed to appeal to Catholic sentiment. In one of them, Napoleon stated: “It has always been my desire to see me among the Breton people, who are first and foremost monarchists, Catholics, and soldiers.” Anyone listening would think that the attempt on his life made him resolve to guide his reign by Catholic principles.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Felice Orsini was tried and sentenced to death. At the trial’s last session, his defense attorney, Jules Favre, read an appeal from the defendant to the Emperor. Incredibly, some argued that the appeal had been authorized (and partially written) by Napoleon III himself.

“I ask Your Majesty to give Italy the independence her children lost in 1849 through the fault of the French. Let Your Majesty remember that Italians, among whom was my father, gladly shed their blood for Napoleon the Great wherever he led them, and they were faithful until his fall. Remember that as long as Italy is not independent, Europe’s tranquility and yours will be only an illusion. Let Your Majesty not reject the last wish of a patriot on the scaffold steps and liberate my fatherland. The blessings of twenty-five million citizens will follow you through posterity.”

It is well to recall that this appeal was read with Napoleon III’s consent and published on his orders in the Moniteur. It turned Philip Orsini into a hero, and his crime became a source of glory for Italian revolutionaries.

Veuillot, seeing how French politics had advanced in a new direction, felt obliged to try to enlighten the Emperor about the error he was making. He requested an audience, and Napoleon III received him. It was the only time they ever conversed. Napoleon tried to show himself as a sincere Catholic. Nonetheless, when Veuillot left the audience, he did not doubt that nothing would stop the Emperor (and former Carbonaro) on the path on which he had embarked.

10 Razones Por las Cuales el “Matrimonio” Homosexual es Dañino y tiene que Ser Desaprobado

An episode known as the “Mortara affair” clearly showed the Empire’s tactics in this new phase. Anna Morisi, a housemaid in the Motara home, baptized Edgardo Mortara, the dying child of a Bolognese Jewish family. Unexpectedly, the child later recovered. On June 24, 1858, the papal government ordered him removed from his parents’ home and given a Christian education. Nothing was more in keeping with Catholic doctrine and the civil law governing the Papal States, which included the city of Bologna.

However, Italian revolutionaries manipulated the situation. The Italian and French Jews protested. Napoleon III saw the incident as an excellent opportunity to weaken the Pope’s position. He promoted a colossal press offensive against the Holy See, ordering pro-government newspapers to stand with the Jews. From France, the debate spread worldwide, giving rise to passionate arguments about history, law, the Jewish question, theology, and everything remotely connected to the case.

With rare exceptions, Catholic newspapers weakly defended the pontifical government. Almost all were tinged with liberalism. They tended to be more supportive of the government than the Church. Some papers were cowed by the attack’s proportions. They lacked the strength to defend the Church’s rights.

L’Univers, however, stood up to the Church’s opponents with its customary ardor. Eventually, Edgardo Motara entered a monastery and was ordained a priest. Thirty years later, he came to thank Veuillot and the newspaper for the firmness with which it had defended his remaining in the Catholic faith.