It was a cool, crisp morning as I drove down a Pennsylvania back road on the way to my first fox hunt. The sky was clear and blue, and the bright sunshine illuminating the frost-covered field brought an agreeable white freshness to the landscape.

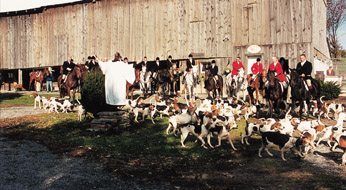

The sights along the way were what one would expect in rural America: small town gas stations, a local post office, and a sign for the local taxidermist. I knew I must be close to my destination, the Rose Tree Fox Hunting Club, the oldest such club in America, having been founded in 1859. There I met my host, Joseph Murtagh, the master of the hounds, known to the other fox hunters as Jody. His tie-pin immediately caught my attention; its golden fox matched the weathervane atop his barn.

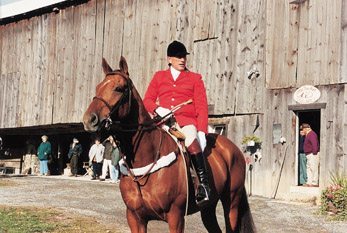

My initial impression was that Jody is typically American, very candid and straightforward. “You can ride along in the truck if you wish to follow the hunt,” he said, “and anytime you care to leave, they would bring you back.” After he mounted his horse to leave, I noticed a subtle change: Joseph Murtagh became rather more distinguished, his deportment more elevated, his manners more refined.

What happened, I asked myself, in that moment between the ground and the saddle? He sat astride his shiny black thoroughbred like anyone about to go for a ride, but there was something different. Was it the scarlet jacket we Americans so often link to a fox hunt, or the snowy white breeches? It could have been his shiny black riding boots or the English hunting horn stuck into his polished brown saddle. He seemed to me the epitome of an English gentleman as the excited hounds were released and bounded all around him. But it was only as the group of hunters trotted off with the clip-clop of hoofs on the frozen ground that I realized what had changed in Jody Murtagh. While in the saddle he becomes part of a tradition that dates back centuries. More specifically, he is the bearer of that same tradition here in America, since he happens to be the fourth generation master of the hounds for the oldest club in America.

Fox hunting has been around since time immemorial but became popular in its present form in England as a means of culling the fox population. Farmers have a hard enough time making ends meet without foxes dining on their chickens and small lambs. What began as a practical solution to a real problem later developed into a tradition rich in ceremony and etiquette.

All of that is now being attacked in England by animal-rights groups and used as a lever for a political agenda. The lower house of the British Parliament has voted overwhelmingly to outlaw fox hunting in England. All that is lacking now is the approval of the House of Lords. It seems only a matter of time, however, before the country most typically known for fox hunting will be obliged to hang up the dignified attire and find other less elevated means of controlling their rust-colored pests.

But before anyone takes down those magnificent fox hunting prints, so often seen in American homes, for fear of suddenly being politically incorrect, hold on. There may be a war against fox hunting in Europe, but this aristocratic sport is still very much alive here in the United States, and, what’s more, numerous Americans are ready to raise a crusade to prevent its being railroaded out of England.

Authentically British

Barbara Murtagh, Jody’s wife, is a distinguished lady full of zest for life. A former fox hunter who has taken some spills, she has long since hung up her riding clothes, but she still relishes having breakfast ready for the hunters when they return. Her eyes sparkle with a childlike enthusiasm when she speaks about fox hunting. I had never encountered anything like it before and was perfectly content just listening.

We found ourselves on a hill, high above south central Pennsylvania when Barbara suddenly shouted with enthusiasm: “There he goes! Tallyho!” Running across the frost-covered cornfield was a red fox, with a tightly grouped pack of excited hounds, Jody, and the rest of the hunters in vigorous pursuit.

Scarlet and black jackets, white breeches and polished black boots — what a sight! This is no ordinary hunt, I thought; this is civilized. It should be, since the fox chase in America meticulously models itself after its British counterpart, with the exception that the fox is not killed in America. Everything else, from the hierarchy of the hunt to the clothing, is authentic.

Hierarchy and Dress Code

As the master, Jody is in charge. After him are the whips or “whipper ins,” who control the hounds, knowing each dog by name and caring for them as one would a child. Yes, they carry a whip, but they do not use it on the animals; they simply crack it to keep the hounds together. The master’s responsibility, with the help of the whips, is simple: find a fox. Once this is done he blows his horn to notify the field master, who then invites the field to join the chase.

The field master’s job is keeping the field of riders close enough to enjoy watching the hounds yet not so close as to interfere with the master or huntsman in pursuit of his hounds.

This strict hierarchy is also accompanied by a formal dress code. Every hunt has two seasons: cub hunting, when young hounds are introduced into the pack, and the formal season. The cubbing season, or “ratcatcher,” allows for less formal attire.

Ratcatcher normally means the use of a tweed jacket with a shirt and tie or turtleneck. November marks the beginning of the formal season and the donning of scarlet coats and white jodhpurs, or riding breeches. Wearing the pinks, as the coats are called, is a privilege one must earn. Others wear black coats. The collars of the coats are full of meaning as well, since different colors signify varying levels in the club hierarchy.

The formal season begins with the traditional Saint Hubert’s day Mass and blessing of the hounds. Saint Hubert lived in the eighth century and was known for his love of hunting stags. One evening while hunting in the Ardennes of northern France, he encountered the largest deer he had ever seen. This deer was different, however.

Between its antlers was a gold cross glowing with an unearthly light. Young Hubert took this as a sign that he was to enter the priesthood. He eventually became the patron saint of hounds and hunting, not only because he had been such a valiant huntsman, but because the hounds he bred are the foundation stock of nearly every hound in the world today.

What to do With all of These Foxes?

Those who think that this is a sport practiced by a few eccentric Americans grasping for some link with bygone days are mistaken. There are currently 177 recognized hunts across America, comprising some 20,000 mounted fox hunters. For the most part they are governed by the Masters of Foxhounds Association of America (MFHA) located in Leesburg, Virginia.

Lt. Col. Dennis Foster, Ret., the executive director of the MFHA, is upset with the unreasonable demands made by the animal-rights activists in England, demands that may end a rich tradition. He has a right to be upset.

According to conservative estimates, there are over 450,000 foxes in England. In an article in the Wall Street Journal-Europe, Frederick Forsyth points out that foxes “breed about 1.5 times their own number in cubs. They grow fast, too” he says. “Born in February, weaned in May, they are ready to hunt, kill, and breed in October. The staple diet is wild rabbit…. In frosty winters they will turn in hunger to poultry and newborn lambs.” The necessity farmers have to cull the fox population is therefore indisputable.

The question, then, is how. Of all the different methods available — traps, neck snares, gas, poison, shotguns, rifles — trained hounds have been the choice of country people. It is a good choice, for it is at once the most humane and the most dignified option.

However, fox hunting “has gone beyond a mere eco-necessity,” Forsyth continued. “It has become a rural society event clothed in ritual and pageantry” which “drives the political left wing to transports of rage.”

Symbols of Restraint

So this is not simply a dispute over the well-being of a poor little fox, but rather a profound sociological difference of opinion. There are those who have a problem with ceremony and manners that elevate and refine. They forget God’s command in Genesis that men rule over every creature that moves upon the earth. It is thus that the refined individual who enjoys the fox chase becomes a symbol of restraint, good manners, and elevation in contrast to those who prefer an untamed and wild nature, symbolic of bad passions left ungoverned.

It is a contrast well illustrated by two elegantly dressed ladies in mink coats I spoke with at this year’s March for Life in Washington. After I complimented them on their neat appearance one of them said, “I feel like carrying a sign that says ‘kill the minks, save the babies.’” The reason, she went on to explain, was simple: “Every animal-rights activist I have ever met was in favor of abortion.”

She did not say that absolutely every animal-rights advocate was in favor of abortion, nor will I. But the acts of violence in England against fox hunters, such as letter bombs and attacks on innocent humans by club-wielding fanatics, leads one to believe that we may soon need an organization to protect men rather than foxes.

What is really necessary, however, is an appreciation for the good manners, decency, and proper deportment displayed by fox hunting enthusiasts all across America.

Nancy Hannum understands this all very well. She is the master of the hounds in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and is considered by other hunt fans as “a member of the old hierarchy” At 81 years of age, she has been hunting since she was four. “She is the only lady I know,” said Barbara Murtagh, “who can command without losing her femininity.” Mrs. Hannum told me that “fox hunting is a family affair, and that is the reason I like it. When the children were young I would walk down to the barn like a ‘grand dame’ with my husband, since they had our horses saddled and ready to go.” Fox hunting teaches discipline and ceremony which shows in the field during a hunt. She also spoke of a young man who had been working for them just a short while: “The change that occurred in him was remarkable,” she said. “He became a gentleman. If you come for a visit,” she continued, “you are treated with respect, and the title of Mr.” This comes from the “association with people who do things right.”

One lady I spoke with said she happened upon a fox hunt while driving home from work one day. “I couldn’t believe my eyes,” she said. “We quickly got our camera out and took a whole roll of pictures. It was so beautiful.”

We cannot deny, then, that the center of the debate over fox hunting is not the killing or mistreating of animals, but an erroneous philosophy and egalitarian vision of the universe which places animals not just on equal footing with, but superior to men. In this worldview, an innocent human life is fair game, but don’t you dare chase a fox.

American Fox Hunters Fight for a Tradition

Dennis Foster is working hard to educate Americans and help hunters in England fight this ban. “Three years ago,” he said, “350,000 people turned out in London for a rally to protest an earlier attempt at a ban.” In May there will be another rally and this year they expect to gather half a million people. He is trying to get as many people as he can to attend this upcoming rally. “Leading up to this march, bonfires will be lit on the hill tops all over the English countryside,” an MFHA press release says, “symbolizing the ancient custom of communicating serious alarm and danger. Similar gatherings and [bonfires] in support of the English countryside will occur on the same day all over the United States. The issue is not fox hunting,” the press release continues, “it is the political agenda of animal-rights organizations that want to change our traditions, lifestyles, and beliefs…” — values that American fox hunters are more than willing to defend.

When I think back to my first hunt, the pleasant impression it made still lingers: images of gentlemen in scarlet coats on horseback as one would only expect to see galloping past thatched roofs in the countryside of England. They are refreshing scenes in a world so little appreciative of ceremony, manners, and etiquette. It is comforting to know that it is not a thing of the past here in America, but even more reassuring to see that Americans are actually defending such values abroad.

While attending that hunt I made a quick call to my mother. After I told her I was watching a fox hunt in Pennsylvania, there was a brief silence. “Where did you say you are?” she asked. “I thought they had those only in England.”

No, Mother, I thought to myself, not any more. They are alive and well in America.