On the Fourth of July, Americans will celebrate our independence and admire the marvelous fireworks. While they do so, the American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property (TFP) will reflect on the issue of flag burning that occurred twenty years ago. At that time, the Supreme Court ruled, only days before July 4, 1989, that flag burning was a “reflection of free speech” and was therefore protected under the U.S. Constitution.

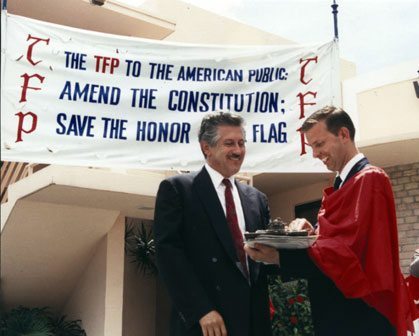

This infamous decision came about because Gregory Johnson, the plaintiff in the decision, pushed the limits of freedom by burning a flag publically during the 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas.After the Supreme Court decision, President George Bush Sr., standing in the shadows of the Iwo Jima memorial, launched a campaign in support of a constitutional amendment to protect the honor of the flag. It wasn’t long before others mimicked Mr. Johnson in acts of protest nationwide. It was then that the American TFP decided to exercise its own “freedom of expression” by traveling the country collecting signatures on a petition drive to support the constitutional amendment proposed by President Bush.

In late July 1989, TFP volunteers hit the streets of New York City and others cities on the East Coast gathering signatures and distributing a flier. Days later, thirty volunteers jumped into a four-vehicle caravan to take our message of honor to the entire country. Besides having a fully equipped kitchen van and camping material, TFP members brought their musical instruments along—complete with trumpets, drums and Scottish bagpipes. This amounted to a veritable miniature marching band.

They first traveled to Florida and then to California, hitting major cities along the way in an effort that is commonly referred to within the TFP as the “Flag Caravan.” Two months later, they returned to New York City after a coast-to-coast campaign that garnered over 120,000 signatures.

Those in Favor

What was most encouraging about this effort was the overwhelming public support. Although equipped with all the necessary material to brave the elements outdoors, caravan members seldom had to camp out. Loyal supporters and patriotic citizens would not tolerate seeing the sunburned volunteers sleeping outdoors, so they provided beds, floor space for sleeping bags or hotel accommodations. The kitchen van was thus used for sandwich breaks at lunchtime on the busy streets of major cities across the country.

Donations in kind such as food and lodging would not have covered the costs necessary to make such a trip possible. The rest of the expenses were acquired in a curious way. After obtaining a signature, members of the TFP would offer a bumper sticker with the message Save the Honor of our Flag, Amend the Constitution to those who signed. The generous donations received were sufficient to cover what was needed for the trip.

The repercussions heard on the street were also good indicators of the appreciation of the public for the effort.

“Give me ten more petitions,” said a burly construction foreman. “I’ve got 72 men working under me and I want them all to sign.” Similar feedback came from a woman who did not need to sign. “Yesterday our whole company signed the petition,” she said.

“Why would anyone want to burn the American flag?” an astonished Italian tourist asked. “If I could, I would sign your petition.”

Value of a Symbol

Not everyone was supportive of the campaign however, and the most common objection came from people who said, “it’s only a piece of cloth.” What people with this mindset fail to understand is the value of a symbol.

The ability to recognize and appreciate the symbolic value of things comes from the fact we are rational human beings capable of abstract thought. However, a person does not need to be a philosopher to understand this. Our language is full of symbolic expressions that take us from the material to the spiritual.

We say a man has a fiery temperament with as much normality as we refer to a snow covered lawn as a blanket of snow. A dog is a symbol of loyalty because as “man’s best friend,” he is always there for you, and a cow represents generosity because it gives everything—its offspring, its milk and itself—for our sustenance.

Other creatures of God are equally useful to symbolize virtues or character traits. While some people are simple as doves, others are cunning as serpents. One man might possess the meekness of a lamb while his neighbor might be courageous as a lion. The idea of purity can be seen symbolically in such things as the lily and the swan for their whiteness. But also in the ermine, which is purported to prefer death rather than soil its fine coat. This is what motivated knights to place this magnificent animal on their coats of arms and a medieval king to adopt the elevated motto “death before dishonor.”

Inspired by God, man is also capable of creating symbols to represent the things they hold dear. A good example of this are flags which have been used since time immemorial to symbolize nations and groups of individuals. The Confederate flag, for example, symbolizes Southern heritage. Shortly after the “Flag Caravan,” certain Southern states were forbidden to fly the Confederate flag over state capitals because it was inaccurately labeled a symbol of slavery. Those who saw no problem with burning our nation’s symbol because it is merely “a piece of cloth” found no problem condemning the other to flames because of what they thought it symbolized. Then there is the “Rainbow flag,” another universally recognized symbol that liberals would defend to the death for what it symbolizes. And finally there is our national symbol, the American Flag, which is the material expression of the American people.

Most Reproduced Photo in History

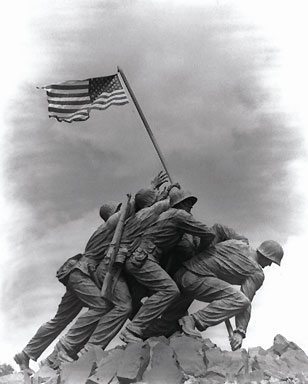

This is the reason for the enthusiasm that Americans had and still have for the raising of our flag on Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima during World War II. It was a daring feat of courageous American soldiers, but it was also an act of ardent patriotism that captured the nation’s imagination. The photo by Joseph Rosenthal of that historic moment happens to be the most reproduced picture in the history of photography.

This was nowhere more evident than in the futile attempts by President Roosevelt to raise money for the war through the use of war bonds. He had made six attempts, some of which included “elaborate shows consisting of stadium appearances, spotlights, music . . . and Hollywood stars.” In spite of the enormous effort, he always fell short until the circulation of the Rosenthal photo. This caused such a sensation at home that the President Roosevelt saw it as a golden opportunity. He then decided to use that picture as “the symbol . . . for the Seventh Bond Tour . . . [and] [P]eople love[d] it.” What the Hollywood crowd was unable to do, a symbol did.The Post Office would go on to make a commemorative stamp of the flag raising and the day it was issued “people stood patiently in lines stretching for city blocks on a sweltering July day in 1945 for a chance to buy the beloved stamp. . . . [Over 137 million were sold.]” They did so because of their pride in our flag—our symbol. The flag represents us, and the editors of US Camera Magazine summed up well what Rosenthal did:

“In that moment, Rosenthal’s camera recorded the soul of a nation.”

The most moving repercussion during the “Flag Caravan” was from an elderly gentleman who approached the young men with tears in his eyes. He, like so many other veterans, became emotional when he saw our campaign. The reason for his tears was simple. “I was there and actually saw the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima,” he said as he wiped away the tears. “I just can’t understand how Americans could have lost the notion of what the flag means.”He was wrong. Not all Americans have lost the meaning of our flag. There are those who recognize its sublime symbolic value even if others think it’s “just a piece of cloth.”