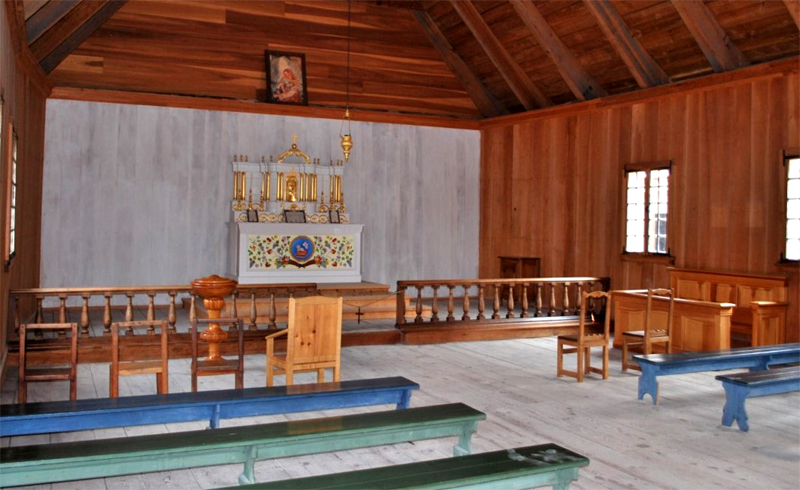

Photo: Ste. Anne’s Church as reconstructed in 1964. Photo Courtesy of Mackinac State Historic Parks Collection.

Frontier Catholics? What frontier Catholics? The idea that there were Catholics on the American frontier is unfamiliar to many. The early history of the United States is often thought of as a product of Protestantism. Our earliest settlers, so the accepted story goes, were English—some Puritans and others Anglican—but all Protestants. Maryland started out as a Catholic colony, but it did not stay Catholic for very long.

The coming of Catholicism to the U.S. is generally associated with the Irish Potato Famine in the middle of the eighteen century. Those immigrants, brutally poor on their arrival, settled in cities along the Atlantic coast, especially New York and Boston. Therefore, early Catholicism in the U.S. is assumed to be an urban phenomenon.

10 Razones Por las Cuales el “Matrimonio” Homosexual es Dañino y tiene que Ser Desaprobado

Obviously, there are a lot of holes in this story, and a little study of the history of Catholicism in America could fill them in. The point is that most people do not think of the Catholic Church as part of the early life of the United States. They do not know of the Jesuit missionaries of lower Canada.

The Church Within the Fort

Those people might be in for a bit of a surprise if they should visit northern Michigan, for at the northern tip of the Lower Peninsula is an outpost of frontier Catholicism. It lies in a reconstructed French fort and is known by its French name of Ste. Anne de Michilimackinac.

Missionaries of the Society of Jesus—commonly referred to as the Jesuits—created a mission called Ste. Marie on the eastern side of Lake Huron on Georgian Bay in modern-day Ontario during the mid-sixteenth century to meet the spiritual needs of the soldiers, fur traders, and the Hurons and other tribes around the Great Lakes. In 1649, the Iroquois began systematic attacks on the Hurons and the Jesuit missions. Among the victims were the eight Frenchmen who came to be referred to as the North American Martyrs.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

As a result of the attacks, the Hurons moved west, to what is now the Michigan side of the lake. Some Jesuits moved with them, establishing a mission that they called St. Ignace after Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, on the Upper Peninsula.

By the early eighteenth century, the French saw a need to construct a wooden palisade fort in the area. The Church of Ste. Anne was first constructed outside of the palisade about 1720. The fort was expanded a decade later and once again in 1744. At the time of the second expansion, a new Ste. Anne’s was built. This second building is the one whose reconstruction can be seen there today.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

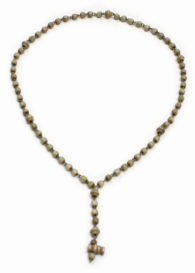

The community was small. Eventually about forty houses would be constructed within the fort. The population was made up of missionaries, soldiers, and merchants. During the summer, the population would swell temporarily as peddlers brought products to the merchants, and the fur traders came in with the produce of their winters’ labors. The sacraments and prayer were very real parts of the life of the fort. On June 23, 2015, the reality of those prayers was shown when the archeologist James Dunnigan found an intact rosary, estimated to be 250 years old on the site of what was once a home within the Fort’s walls.

The reconstruction of Ste. Anne de Michilimackinac as it stands today is a rough, rather crude structure. The original old building was torn down long ago. The parish however did evolve over time to become something larger and more ornate.

The British won the fort from the French in 1760 during the French and Indian War. They later abandoned Fort Michilimackinac, which included Ste. Anne’s. The old church was dismantled and moved to the new Fort Mackinac on the nearby (and more easily defended) Mackinac Island.

By 1821, the relocated building was gone, although the historical record does not record whether it was demolished, burned down, or met some other fate. A replacement church building was completed in 1827, which was, in turn replaced in 1876. Today’s visitor to Mackinac Island will find the parish still very much alive in this pretty little Gothic building.

Reconstruction

In 1959, the State of Michigan decided to reconstruct the French fort as a stop for tourists crossing the new Mackinac Bridge. An archeological process began that continues each summer.

In 1964, they began to rebuild the church building at the fort. The location was known because a map of the fort had been drawn in 1766. The archaeologists found evidence of a small building built about 1720 that was replaced by a larger one around 1740. Other than the fact that it was constructed of squared off logs laid horizontally, no one knew for sure what it had looked like.

Fortunately, about three months before reconstruction was to begin, Michigan historians heard about an existing Jesuit church built only a few years later in rural Quebec. A further coincidence connected the two buildings. The Quebec church had been constructed in 1747 under the direction of Fr. Claude Godefoy Coquart, S.J., who had served at the fort while Ste. Anne’s was being built. Using the Quebec Church as a guide, reconstruction began.

During the nineties, the reconstructed Ste. Anne’s took on the form we see today. The box pews found in Quebec and reproduced for Ste. Anne’s were determined to be later additions as was a statue of Saint Anne that had been placed there. Both were removed and the pews replaced by benches. However, a “Wardens’ Pew,” common in both French and colonial churches for laymen of special status was built and placed in the correct position.

The Beauty of Worship

Two important items were missing from the reconstructed church. There was neither a baptismal font, nor was there a confessional—omissions that the eighteenth century Jesuits would certainly not have made. Examples from the time were copied and installed. Another very important correction was the replacement of the very simple and inaccurate altar installed in 1964. Historians found other altars from Jesuit churches of the period. They were considerably more ornate than the table that had been placed there originally.

The altar makes the greatest impression on entering Ste. Anne’s. At first, it seems out of place in so simple a building. The altar is lovely with its painted Agnus Dei, gold leaf, and golden crucifix, tabernacle door, and candlesticks, surmounted by a kind of crown-like structure with a cross at the top. While not as ornate, the turned wood baptismal font and paneled confessional are still items of craftsmanship and simple beauty.

Science Confirms: Angels Took the House of Our Lady of Nazareth to Loreto

It may take a minute or two to process this information, but the devout Catholic will sense the meaning of this, even if it is somewhat difficult to put into words. Everything that has to do with the sacraments is beautiful. The walls and the roof can be plain; all they do is keep out the weather. The benches only provide a bit of comfort for the worshippers.

However, the baptismal font and the confessional bring us to God, a matter of eternal importance. The altar is God’s alone, the place where His sacrifice will be celebrated on a daily basis, the throne on which He will repose until the next Holy Mass.

The altar, and to a lesser extent the font and the confessional are the reasons that this place is here. This is no gathering place, no social hall, no venue for whatever entertainment may be available. This is holy ground, the place in which God in His Massive Benevolence comes to us, just as He came to the soldiers, fur traders, and villagers almost four centuries ago.

Oh, come, let us adore Him!