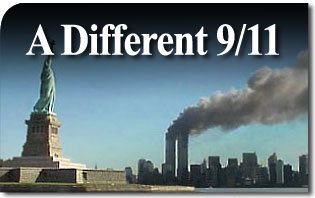

This past September 11, as Americans recalled their dead and expressed outrage at the cowardly terrorist attacks of 2001, the Left around the world shed bitter tears for an altogether different 9/11.

This past September 11, as Americans recalled their dead and expressed outrage at the cowardly terrorist attacks of 2001, the Left around the world shed bitter tears for an altogether different 9/11.

Forty years ago on September 11, 1973 the Chilean military staged a coup d’etat against the government of Salvador Allende, putting an end to the so-called “Chilean way to socialism.”

Let us quickly review the events leading up to that coup.

“Revolution in Freedom”

In 1964, Eduardo Frei Montalva, a Christian Democrat leader and disciple of Jacques Maritain, was elected president of Chile.

The slogan, “Revolution in Freedom” summarized his 5-point political program: economic development, education and technical training, solidarity and social justice, political participation and people’s sovereignty.

This program was designed to put Chile on a “non-capitalist” road to development. As soon as they came to power, the Christian Democrats began a policy of “popular promotion” through a kind of “communitarianism” by establishing a network of “neighborhood committees” and “mothers’ centers.” This policy was complemented with more radical measures in rural areas by encouraging the formation of farmworker unions and implementing a 1967 land reform law, which confiscated private lands without fair compensation to the deprived landowners under the pretext of forming small, family-size farms and integrating landless peasants into cooperatives.

In fact, as the late Brazilian TFP director Fabio Vidigal Xavier da Silveira denounced in his book Frei, the Chilean Kerensky (which likened the policies of Eduardo Frei with those of Kerensky in Russia), that “moderate” reform program actually paved the way for socialism.1

Christian Democrat Connivance

In September 1970, Marxist Salvador Allende rose to power in Chile thanks to the collaboration and complicity of Christian Democrats and large sectors of the clergy.

He was the candidate of Unidad Popular [Popular Unity], a leftist political coalition that included the Socialist, Communist, and Radical Parties, the Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitario (MAPU – Popular Unitary Action Movement)—an offshoot of Christian Democracy—and several other groupuscules, as well as “the more advanced and progressive sectors of political Catholicism and secularist quarters of the professional and intellectual petty bourgeoisie.”2

Allende’s election reverberated around the world, as it was the first time an officially Marxist candidate gained power through free elections. The international press sought to inculcate the idea that the victory of the leftist coalition in Chile presaged other communist advances in sister nations on the Latin American continent.

In reality, the “victory” of the Marxist candidate resulted more from a political maneuver than from a successful election.

Indeed, the figures prove that Allende, the Unidad Popular candidate, had received nothing even remotely close to a majority in the elections: he garnered just 36.3% of the vote, to Jorge Alessandri’s (the centrist candidate) 34.9%.3

The Chilean Constitution provided that when election results were extremely close, as they were between Allende and Alessandri—a mere 1.4%—it was up to Congress to freely choose the President of the Republic from among the most voted-for candidates.

The fate of the election thus lay in the hands of the Christian Democrat congressmen, for if they sided with Alessandri, he would have an absolute majority in Congress. However, the Christian Democrats cast their lot with the Marxist Allende, thus giving him the electoral win.

“No Weapons or Beards Just Tricks”

Speaking on May 21, 1971 at a plenary session of the Chilean Congress, Salvador Allende explained what the “Chilean way to socialism” would be like. He said Chile had to find a new way to “build a socialist society,” “our own revolutionary, pluralistic way” different from the Russian and Chinese ways. It would be a new model of transition to a socialist society, “a democratic, pluralistic and libertarian model… respectful of the rule of law, institutions and political freedoms.”4

Along with this reassuring speech, Allende at first limited himself to implementing existing socialistic legislation approved earlier by the government of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei.

This maneuver had the effect of numbing reactions to the socialist regime.

In October 1971, the Chilean TFP, then in exile, released a document titled “The Chilean Way: No Weapons or Beards, Just Tricks.” The manifesto made a detailed analysis of how communism—despite having been rejected by a majority of the population—was being inexorably imposed on the country. The great trick of Unidad Popular for pulling this off was the enveloping of opponents in a “numbing and insulating panic.” The anti-communist majority felt inhibited by fear of reprisals and by a false hope that Allende would not take his program to its final consequences. As a result, many Chileans cared only about peacefully emptying, to the last drop, the cup of material well-being that the progressive application of the Marxist program was gradually eliminating.5

The “Chilean way to socialism”

The thousand days of the Salvador Allende government were a far cry from the much-trumpeted “revolution without guns.”6

In July 1971, Allende nationalized copper mining. He went on to confiscate the farms, increase State control over businesses and banks, nationalize foreign companies and implement “the redistribution of wealth” through exhorbitant taxes.

Meanwhile, in typically Leninist and Maoist style, the Marxist-socialist coalition was working in tandem with the government. Factories saw the creation of “workers’ committees”—true Soviets—which then wrested control over administration and production, reducing these enterprises to chaos. In the countryside, farms were invaded by agitators, crops were destroyed and livestock cut down. Food scarcity ensued.

The government’s attempt to restructure the economy led to rising inflation. In December 1972, speaking before the United Nations’ General Assembly, Allende denounced an “international aggression and economic boycott” against his country. Finally, a few months before the coup, a prolonged strike by teamsters opposed to his nationalization of the country’s transportation left food markets without supplies. With little to nothing left to sell, shop owners joined the protests. City and rural workers—precisely those who supposedly “benefitted” by socialization—began to revolt against their increasing misery. Housewives too poured in to the streets, banging their empty pots. Poverty spread across the nation like gangrene. Unrest became general and massive strikes paralyzed the country.

The economic and social crises triggered a political one. The combined effects of the social, political and economic crises caused widespread chaos, and the country was on the brink of collapse.

September 11, 1973

The rest of the story is already known. On September 11, 1973 the Armed Forces intervened with a coup headed by General Augusto Pinochet, who deposed the Marxist president and put an end to the “Chilean way to socialism.”

Given the growing tension in which the country had lived for months, the coup was not a surprise. Allende’s overthrow was welcomed by a majority of the Chilean population, hostile to his socialist reforms and tired of the economic hardship and social unrest he had inflicted on them.7

At dawn on September 11 (coincidentally also a Tuesday, as in the attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon) Navy ships that had sailed the day before from Valparaiso to participate in a joint maneuver with American vessels returned to their base. A few cannon salvos sufficed to give the Navy control of the port, city streets, public buildings and military installations, as well as communication centers. It was 6 o’clock in the morning.

An hour later, the bombing of La Moneda Palace, the seat of government, began. Army troops and Carabineros (Gendarmerie) surrounded the building where the president was and gave him an ultimatum. When he refused, the palace was stormed. After hours of useless resistance, Salvador Allende committed suicide with the gift submachine gun he had received from his friend, Fidel Castro—supposedly to be used in the defense of the Chilean Socialist Revolution.

With the end of the Chilean socialist experiment, communism lost ground throughout South America.

Footnotes

- Alexander Feodorovitch Kerensky, the “moderate” socialist who governed Russia after the fall of the Tsarist regime, set the stage for the outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution and for Lenin’s rise to power. In like manner, nearly fifty years later, Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei paved the road for Marxist Salvador Allende to become president of Chile.

- Oscar Soto Guzmán, Allende en el Recuerdo ─ Golpe 40 Años, in RED – Diario Digital

- Cf. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, “Toda a verdade sobre as eleições no Chile,”

- Salvador Allende, La “vía chilena al socialismo”

- Cf. Tradicion Familia Propiedad, 1967/1974 ─ De Frei a Allende ─ La TFP chilena y sus cohermanas ante el crepúsculo artificial de Chile

- La ‘vía chilena al socialismo’, el fin de la inocencia, Lantxabe

- La ‘vía chilena al socialismo’, el fin de la inocencia, Lantxabe