Before Pius IX had restored the episcopal hierarchy in 1853 with the papal bull Ex Qua Die (1853), Catholics in the Netherlands were forbidden by law to publicly manifest their Faith. The Church was reduced to scattered groups, which would secretly gather for Mass celebrated by fugitive priests inside sheds, attics and warehouses.

The Netherlands was left without bishops after the last Vicar Apostolic of the Netherlands signed a notarial act in 1709, resigning from the mission entrusted to him by the Holy See. Thus, many Catholics in the Missio Hollandica were deprived of the sacrament of confirmation.1

Only after the French Revolution, did the status of the Church in the Netherlands improve slightly, whereby Catholics in the nineteenth century started to mobilize against the persecution of the Church.

This fight was initially led by the convert Joachim le Sage ten Broek. In 1818, he founded the monthly magazine De Godsdienstvriend and in 1835 the weekly magazine Catholijke Nederlandse Stemmen. The Catholic leader frequently engaged in polemics with Protestants and also inspired the founding of other Catholic magazines and newspapers in the Netherlands.2

An important milestone was achieved by Fr. Franciscus Jacobus van Vree, who later became the first Bishop of Haarlem after the restoration of the episcopal hierarchy. He founded De Katholiek in 1842, the country’s first theological magazine. Others followed his good example. In 1845, Fr. Josse Antoin Smits and Dr. Johannes Wilhelmus Cramer started the daily newspaper De Tijd, which became the first Catholic newspaper in Amsterdam.

The rise of Catholic magazines and newspapers was crucial for the Catholic revival of the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, many publications deviated from the right path by promoting liberal principles.

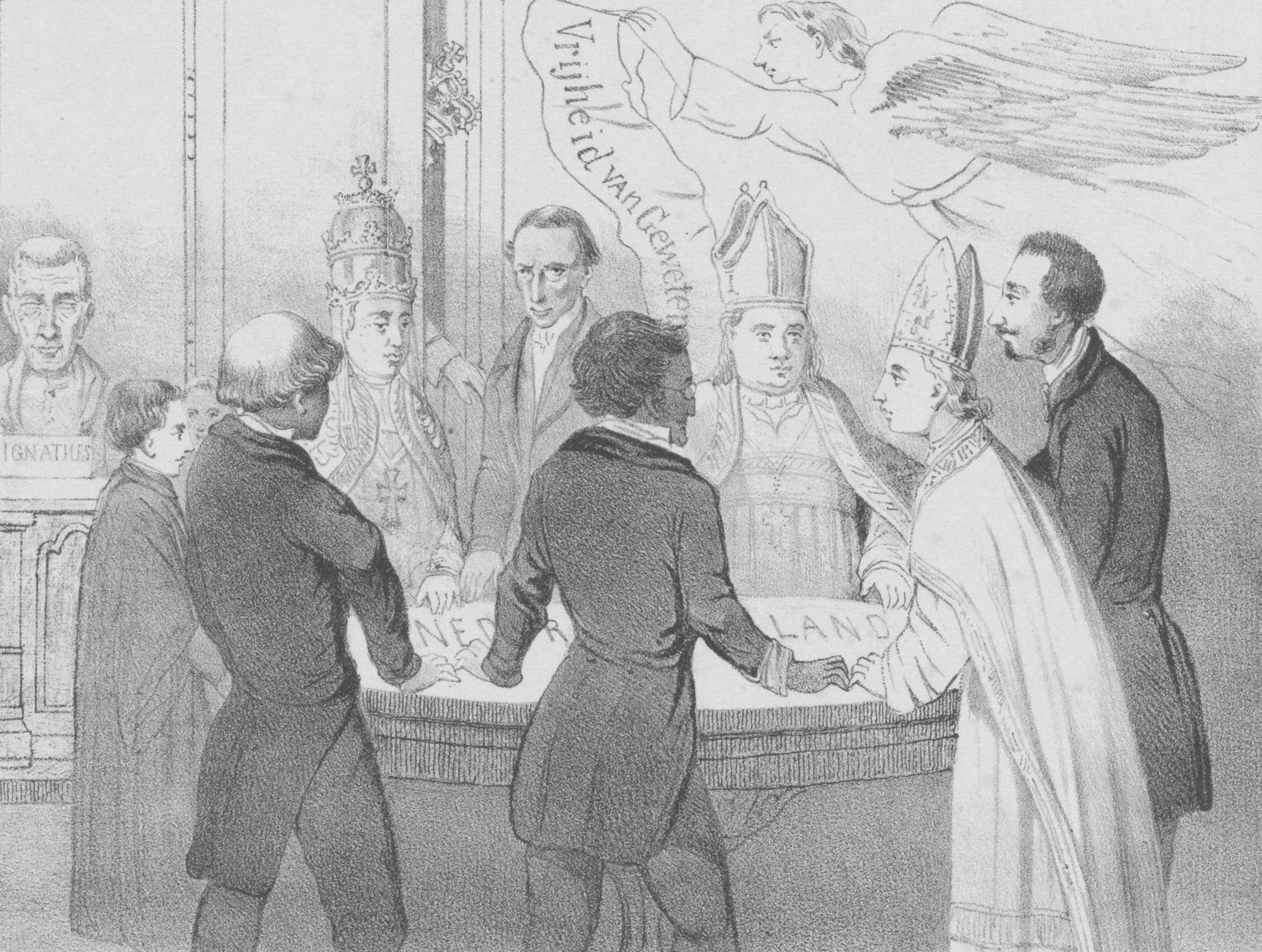

The chief heresy behind the deviation was liberal Catholicism, a system of errors which sought to reconcile the principles of liberalism, particularly the separation of church and state, religious liberty and freedom of conscience, with the Catholic faith. Its origin traced back to France, where Fr. Félicité Robert de Lamennais, Fr. Henri-Dominique Lacordaire O.P. and Charles de Montalembert disseminated these errors in the daily newspaper L’Avenir.3

Among Dutch Catholics in the first half of the nineteenth century, the followers of Fr. Lamennais were much more numerous than the Ultramontanes who upheld tradition.4 Thus, Le Sage ten Broek in De Godsdienstvriend echoed the French priest’s errors with the following declaration:

“Religion must be free in order to possess a convincing power. Truth must owe its triumph solely to itself: therefore, error must also be free… If truth and error are equally free, both completely free, then it cannot remain doubtful for long which of the two is the truth. Therefore, we desire not only the complete and universal freedom of Catholicism, but also of all other religions, so that truth may triumph through God and freedom.”5

Gregory XVI condemned the errors of liberal Catholicism in the encyclical Mirari Vos (1832), which he called “that absurd and erroneous opinion, or rather insanity, that liberty of conscience must be claimed and defended for anyone”.6 But his denunciation had only a negligible effect on Dutch Catholics. Most simply ignored the encyclical, and the Catholic press continued in its liberal direction.7

The influence of liberal Catholicism manifested itself especially in politics. To secure freedom for the Church, these liberal Catholics formed an alliance with the liberals, which resulted in the constitutional reform of Thorbecke in 1848. Their political ambitions were formulated in an article from De Tijd on March 21st, 1848, which supposedly “expressed the opinion of the entire Catholic population of the Netherlands”:

“We have the right to freedom of confession and worship… Equal protection must be granted to all religious denominations. That protection must never be preventive; after all, preventive protection is—or degenerates into—domination. Therefore, the state must never be allowed to interfere in the internal affairs of any denomination.”8

Some Catholics opposed the dominant influence of liberal Catholicism. Among them was Dr. Cramer, who definitively broke from De Tijd in 1857. He opposed the liberal policies of Mgr. Smits, who hindered him from publishing articles with Ultramontane leanings.9

After 1853, the tide turned in favor of the Ultramontanes. Several factors contributed to this change. Catholics became scandalized by the increasing anticlericalism of the liberals. They opposed their liberal religious education policies and how they dealt with the “Roman question,” which disputed the temporal power of the popes.

In addition, Catholics followed the pontificate of Pius IX, which increasingly took a more Ultramontane direction after the Risorgimento had revealed its true colors as an attack on the papacy. Louis Veuillot and his daily French newspaper L’Univers also was a factor of change and became the leading model for most Catholics in the Netherlands.10

With the dogmatic encyclical Quanta Cura (1864) accompanied by the Syllabus Errorum (1864),11 Pius IX brought an end to the crisis of liberal Catholicism in the Netherlands.12

Footnotes

- Rogier, L. J. & De Rooy, N. (1953). In vrijheid herboren. Katholiek Nederland, 1853-1953. Den Haag, the Netherlands: Uitgeverij Pax, p. 13-17.

- Albers, P. (1904). Geschiedenis van het herstel der Hierarchie in de Nederlanden II. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: L.C.G. Malmberg, p. 8-11.

- Pijper, F. (1921) Het modernisme en andere stroomingen in de Katholieke Kerk. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: S.L. van Looy, p. 14-16.

- Among the followers of Fr. Lamennais were Mgr. van Bommel, the Bishop of Liège and Fr. Roothaan S.J., the twenty-first Superior-General of the Jesuits: De Jong, J. (1949). Handboek der Kerkgeschiedenis IV: De Nieuwste Tijd (1789–1949) (4th ed.). Utrecht - Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Dekker & Van de Vegt, p. 83.

- Taken from the article De ware Liberalen kunnen de vijanden van het ware Catholicismus niet zijn, published by De Godsdienstvriend 26 (1831), p. 319; Gorris, G. (1949). J.G. Le Sage ten Broek en de eerste faze van de emancipatie der Katholieken II. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Urbi et Orbi, p. 216.

- Denz. 1613, taken from the thirtieth edition (pre-1963) of Fr. Henry Denzinger’s Enchiridion Symbolorum et definitionum (1954).

- Nuyens, W. J. F. (1878). Herinneringen aan de April-beweging van 1853. Onze Wachter, 1878 (1), p. 110.

- Nuyens, W. J. F. (1885). Geschiedenis van het Nederlandsche Volk van 1815 tot op onze dagen. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: C.L. van Langenhuysen, p. 98-101.

- Rogier, L. J. & De Rooy, N. (1953). In vrijheid herboren. Katholiek Nederland, 1853-1953. Den Haag, the Netherlands: Uitgeverij Pax, p. 292-295.

- Ibid., p. 511-512.

- There is no doubt that the condemnations in the encyclical Quanta Cura (1864) are dogmatic. This was the view of Cardinal Manning, who in The Centenary of Saint Peter and the General Council: A Pastoral Letter to the Clergy (1867), p. 34, referred to the encyclical as “the supreme teaching of the Church.” Cardinal Mazzella S.J., Cardinal Newman and Fr. Scheeben also confirmed this in their works. Whether the accompanying Syllabus Errorum (1864) is infallible is less certain: Washburn, D. C. (2016). “The First Vatican Council, Archbishop Henry Manning, and Papal Infallibility.” The Catholic Historical Review, 102(4), p. 740–741. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45175598.

- De Jong, J. (1949). Handboek der Kerkgeschiedenis IV: De Nieuwste Tijd (1789–1949) (4th ed.). Utrecht – Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Dekker & Van de Vegt, p. 118-119; Rogier, L. J. & De Rooy, N. (1953). In vrijheid herboren. Katholiek Nederland, 1853-1953. Den Haag, the Netherlands: Uitgeverij Pax, p. 164-165.