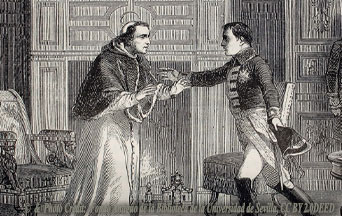

In 1804, First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor of the French. A few days before promulgating the laws establishing the Empire, Napoleon conferred with Giovanni Battista Cardinal Caprara, the Papal Legate. Napoleon asked the legate to sound out the Holy Father about the possibility of consecrating him as Emperor in Notre Dame Cathedral.

The request was manifestly inappropriate. Several issues had arisen between the Holy See and France since Napoleon began the ostensible policy of rapprochement with the Church. One of these was the Concordat of 1801, which still contained the “organic articles” that Napoleon added to it without Rome’s knowledge. That process was repeated in northern Italy in 1805. After being approved, a similar concordat was published with unilateral changes to the text. New frictions arose with the complete remodeling of the Holy Roman German Empire. The First Consul tried to force the Holy See to modify diocesan boundaries to match the borders of the countries he had created.

Why America Must Reject Isolationism and Its Dangers

However, despite the repeated failures of his appeasement policy, Pius VII authorized the opening of negotiations. These were conducted in Paris by Cardinal Caprara, who was always eager to satisfy Napoleon’s wishes, and in Rome by the French Ambassador, Cardinal Joseph Fesch, Napoleon’s uncle.

Napoleon wasted no time. He avoided burning issues with the excuse that they could be dealt with during the Pope’s stay in France. He limited the talks to problems concerning the consecration and hastened Pius VII’s trip. The Holy Father left for Paris on November 2, 1804. Everything happened so quickly that the new consecration ritual was not ready. A new ritual was required because Napoleon refused the Roman protocol and the one the kings of France had historically used in Reims.

No friction points were resolved during the Holy Father’s stay in France. Pius VII returned to Rome, leaving practically all of them unresolved. However, one delightful surprise encouraged the Pope. The French people accorded him a filial and enthusiastic welcome from the moment he crossed the border. In this respect, his trip was an absolute triumph. It was a public demonstration that France remained profoundly Catholic despite the Revolution’s efforts to strip it of its faith. In Paris, the poorest neighborhoods were the ones that celebrated and honored the Holy Father most enthusiastically. This reception alarmed Napoleon.

In response, the imperial government initiated a policy to channel the people’s allegiance to Catholicism to Napoleon’s advantage. Such a policy would have failed if the hierarchy had opposed it. Unfortunately, for the most part, the episcopate yielded to the Emperor’s impositions. Cardinal Caprara was always ready to approve whatever Napoleon wanted on behalf of the Holy See.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

Napoleon had a catechism composed, corrected it himself, and imposed its use throughout France. It is the famous Imperial Catechism. It was instituted with the abject collaboration of Most Rev. Etienne-Alexandre-Jean-Baptiste-Marie Bernier, Bishop of Orléans. It treats dogma superficially, as though they were sources of idle discussion among theologians, and of no importance to the life of the faithful. Conversely, the Imperial Catechism abundantly describes and emphasizes the people’s duties to submit to civil authority.

All existing Catholic newspapers in France were merged into one to better direct and control the clergy. The Journal des Curés only published articles and news that contributed to the revolutionary formation of churchmen. Its tone was in line with the spirit of the Imperial Catechism.

Napoleon admired Charlemagne as a shaper of Christendom. Napoleon sought to imitate him by consolidating the Revolution and spreading it across the Continent. He wanted to force the Pope to recognize his mission and fully support it. In northern Italy, he repeated the processes applied in France, all the while minding the reactions of public opinion. After crowning himself King of Italy in 1805, he introduced the French Civil Code there. He constructed a new set of statutes that facilitated the domination of the Italian clergy and hierarchy.

The Pope protested, but to no avail. Once, with his usual impertinence, Napoleon upbraided Pius VII, complaining that Rome “follows a policy which, while good in other centuries, is no longer appropriate to the century in which we live.” He occupied cities in the Papal States, crossing the Papal lands with troops to invade other countries. Even after altering the Concordats, Napoleon continually violated them when it suited his whim. All the while, he sought to force his desires on the Holy See, using all manner of pressure.

Pius VII finally recognized that he could no longer give in. Exasperated with Papal resistance, Napoleon demanded that the Holy See incorporate itself into the French political system. Unsatisfied with the Pope’s answer, he decided to use violence. On February 2, 1808, French troops commanded by General Sextius Alexandre François de Miollis occupied Rome and disarmed the papal army, which had been ordered not to defend itself.

Gen. Miollis initially tried to placate Roman society by offering them frequent entertainments. However, the General’s receptions gradually emptied because Pius VII forbade churchmen to attend. Loyal laypeople refrained from them as well. The General’s parties were attended only by families of French officers and diplomats, with one or two Italian guests. To win over the citizenry, the invaders organized grand festivities during the carnival, but the Roman people supported the Pope and stayed away.

Read About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Read About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

On May 16, 1809, Napoleon annexed the Papal States to the Empire. When Pius VII saw the tricolor flag flying over the Castle of Saint Angelo, he signed a bull prepared by Cardinal Bartolomeo Pacca, his Secretary of State. This document excommunicated “this sacrilegious violation’s usurpers, promoters, advisers, adherents and executors.” At two a.m. on July 6, General Étienne Radet stormed the Quirinal Palace, abducting both the Pontiff and Cardinal Pacca.

Arresting Pius VII was one of Napoleon’s great errors. He always denied having ordered it. Years later, imprisoned in Saint Helena, he tried to justify himself by denying responsibility for Miollis and Radet’s actions. Nonetheless, the Pope’s firm attitude toward Napoleon’s efforts to dominate the Church made such violence inevitable.

That violence against the Vicar of Christ caused Spain—which had chaffed under Napoleon’s rule—to gain a new soul for the fight. French public opinion had often given proof of its attachment to the faith. Many laymen, loyal to the Pope, also reacted against the Emperor’s religious policy. They faced extreme danger and defied Joseph Fouché’s police. Ultramontanes united and facilitated the exercise of Church government by establishing a secret communications network between the imprisoned Pope and the faithful religious authorities.

Photo Credit: © Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla, CC BY 2.0