This article is part two of a three-part series on Americanist Heresy. It is based on the author’s meeting on February 12, 2025, at the American TFP’s headquarters in Spring Grove, Pennsylvania. Click here to read part one or three.

* * *

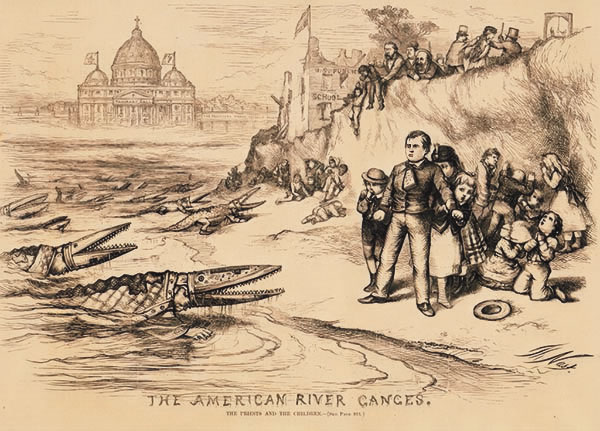

This article opens with an illustration to which any Catholic should object. It is an anti-Catholic cartoon published in 1871.

This cartoon appeared in the Harper’s Weekly Magazine. Its artist was Thomas Nast. Nast’s cartoons were so unpleasant that we derive the slang term “nasty” from his name. It is titled “The American River Ganges,” referring to the sacred river in India. The subtitle reads “The Priests and the Children.” If you look closely, you can see that the crocodiles are actually bishops wearing their vestments and miters crossing the river separating the Vatican from America. The stalwart young man preparing to protect the children is a public school teacher. In Nast’s mind, the bishops are trying to infest American children with Catholicism.

Why America Must Reject Isolationism and Its Dangers

There can be little doubt that Mr. Nast was thinking about bishops in the mold of “Dagger John” Hughes of New York and John Nepomucene Neumann of Philadelphia. By the time Harpers published the cartoon, both men had passed away, but memories of these stalwart defenders of Catholic children’s rights to a Catholic education didn’t fade quickly. Indeed, they inspired generations of bishops and priests who established the only school system to give America’s state-supported schools a real challenge.

Rampant Anti-Catholic Bigotry

This cartoon provides essential insight into the social standing of Catholics in the United States during the late nineteenth century.

To say that the United States had a deep strain of anti-Catholicism would be an understatement. Much of that sentiment remains. Even in the twenty-first century, that battle remains. It played out again when the Supreme Court recently ruled that Oklahoma Catholics do not have the right to create a state-funded Catholic charter school.

We will not discuss anti-Catholicism itself, but we have to begin there. Much of the controversy over the Americanist Heresy involves Catholics’ reactions to it. Several members of the Catholic clergy—high and low—were on both sides of the dispute.

However, the struggle to defeat anti-Catholicism wasn’t just about schools. Many American Protestants had been raised on half-baked tales that Catholics worshipped the saints and pieces of bread. Catholics were ruled by the Pope and would be disloyal to the United States if the Bishop of Rome ordered it. Catholicism, to many Protestants, was a heinous mixture of “real” Christianity with centuries of European superstition. Allowing such people to gain a foothold would endanger America’s greatness.

A Culturally and Physically Divided Church

However, anti-Catholic bigotry was not the only problem that the Church faced in the United States. Any discussion about the Catholic Church in the United States during the nineteenth century must take place against a complex backdrop.

The Catholic laity tended to divide themselves. Three easily defined groups existed—the Irish, the Germans, and everybody else. The vast majority of the Irish migrated to America during the Potato Famine of the 1840s, living primarily in the cities in which they arrived—New York or Boston. The Germans had arrived about the same time but were not as poor, so they could decide to settle in eastern Cities or migrate further into the Midwest. Most of the “everybody else” consisted of small pockets of French settlers along the Gulf Coast or those that drifted from French Canada into New England, New York and Michigan. There were also scattered pockets of Portuguese fishermen in port cities.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

Another significant development was that the country was constantly expanding westward. Stories of gold in California, silver in Nevada and various metals in the Rockies attracted many, especially those with a mining background. Farmers were drawn to the cheap—or even free—land that lay forever to the west. Catholics were not immune to such inducements. Catholic immigrants with skills in blacksmithing, carpentry, leatherwork or printing (among others) settled wherever they could parlay those skills into prosperity.

So, there were many areas in which a relative handful of Catholics lived in predominantly Protestant villages and towns.

Poor Communications and a Shortage of Priests

Another factor complicating the situation was that communications beyond local areas were almost non-existent. There were national magazines, but these were limited to the relatively well-off and only came out monthly. The telegraph extended nationwide but was very expensive. Telephones existed, but a national telephone system would have to wait for the twentieth century. There was a transcontinental railroad, but it took several days to get from coast to coast, and large areas to the north and south of the main railroad line were still unconnected except by horse-drawn wagons.

All of these factors created massive problems for the Catholic hierarchy. However, the biggest issue was an enormous shortage of priests. Finding ANY priest to offer Holy Mass for the thinly settled Catholic population was daunting. Moreover, ensuring those priests were consistently orthodox was virtually impossible.

In the thinly-populated United States, individualism flourished. It was easy for a relatively unschooled Catholic to adopt the practices and beliefs of his Protestant neighbors, especially if a spellbinding preacher came along holding “revival services” in a massive tent on the outskirts of town. These combinations of entertainment and fundamentalism attracted many Catholics, especially if the lack of priests meant that they hadn’t attended Holy Mass in months or even years.

Uncertain Prospects

Topping off all of these thorny issues was the fact that Christianity, generally, was in decline at the end of the nineteenth century. A belief in science, represented by Charles Darwin’s theories, was beginning to displace religion as a guiding philosophy. At the same time, Karl Marx’s Communist ideas began to take hold among radicals on both sides of the Atlantic.

Read About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Read About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Of course, many American Catholics persevered in the Faith. Those who lived in a community of Catholics had a fair—and increasing—chance to go to the Sacraments regularly and get their children into solid Catholic schools. Missionary priests strove diligently—some even working themselves to death—to bring the Faith to widely scattered flocks.

Heresy thrived under conditions such as these, and the fertile American Midwest would breed a bishop who would spread Americanist tendencies worldwide. His name was John Ireland, the Archbishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota. His role in the Heresy—and those of his opponents—will form the fourth installment of this series.