the Assignment of Women

in the Armed Forces,

Washington, D.C.

Testimony of Colonel John W. Ripley

26 June 1992

COLONEL RIPLEY: I, too, would like to begin with prepared remarks.

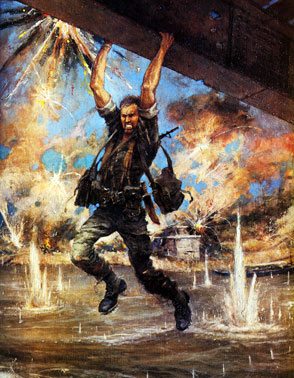

Ladies and gentlemen of the Commission, I’ll start with my background. Very briefly, my association with combat. I served my first combat tour as a young Marine captain company commander of a rifle company for a year in Vietnam, along the DMZ; from Khe Sanh, virtually all of the fire bases, over to the Tonkin Gulf, Con-Tien, Rockpile, Khe Sanh and the jungles in between.

My next tour was with the Vietnamese Marines four years later, where I served in virtually the same area. At the time, Khe Sanh was abandoned, and I had the distinction of being the last American there, having been shot down there twice on two consecutive days.

I also served a tour with the British Royal Marines, where I commanded a rifle company in 4/5 Commando, deployed with them to the Arctic for two years—correction, two winters—and during that same tour, I deployed to Malaya, where I served with the 1st of the 2nd Gurka Rifles and 40 Commando on a post-and-station tour that, to my surprise, in the jungles of northern Malaya, also included combat. I wasn’t supposed to know that.

I had been trained exceedingly well by the Marine Corps. I am one of two Marines who have completed all four schools preparatory to reconnaissance training; airborne, scuba, jump, trained with the Navy SEALs at the time they were not SEALs, they were UDT, and, finally, the British Royal Marine Commando Course. There are only two present active-duty Marines so designated.

I give you this information simply to acquaint you with my background and also to say that I feel I have some degree of expertise in this subject, although I personally do not like the term “expert.”

During my tenure as a company commander in Vietnam, my company was lost three times over. At the time, my rifle company weighed out at about 210 Marines; 212 perhaps. When you added your attachments, your engineers, scout dogs, and others that joined that company, it could be perhaps another 25, 30 Marines in addition.

I lost my company 300 percent in that 11 months, killed and wounded: 13 lieutenants killed, all my corpsmen, three senior corpsmen and an additional 15 corpsmen, killed and wounded.

(5:34 p.m.)

COLONEL RIPLEY (Continuing): I feel I have a basis upon which to comment, and I would like to read this statement: First of all, this subject should not be argued from the standpoint of gender differences. It should not be argued from the standpoint of female rights or even desires.

As important as these issues are, I think they pale in the light of the protection of femininity, motherhood, and what we have come to appreciate in Western culture as the graceful conduct of women.

We simply do not want our women to fight. We simply do not want them to be subjected to the indescribable, unless you have been there, the horrors of the battlefield.

The oft-intoned surveys that we have heard have yet to show you even a reasonable minority of women who feel that they belong in combat units. Survey after survey and question after question, ad nauseam, is answered with the overwhelming majority, around 97 percent, with “No, I do not want to be in a combat unit. There is no purpose for me being there,” and the only purpose which has been stated, as we know, is for that pathetically few who strive to gain higher command and feel that they must have served in a combat unit to achieve command, or perhaps higher rank.

The issue then becomes, “I want to be in a combat unit or to serve in that unit, to serve in combat, to qualify myself for promotion,” and this, I must tell you, is the worst possible reason, because it is self-serving. It is self-aggrandizing. The only purpose is to further the interest of the individual, as opposed to improving the unit.

Now, combat Marines will tell you that any leader, junior or senior, who focuses on himself, as opposed to the good of the unit, is completely worthless as a leader and he will never be followed willingly, and he will never gain the respect of his Marines.

Combat Marines will also tell you that they distrust any leader who puts his own wellbeing and his own ambition ahead of the mission of the unit, or the good of the unit. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is precisely what is happening here. These extraordinarily few would-be generals are saying, “It is more important for me to be in a combat unit, so that, I may profit from that and become promoted than it is for the unit to be combat effective, combat ready, and successful in combat.” And that is precisely what they are saying. That’s exactly what this issue is. (It comes down to, “My ambition, my personal needs, are greater than the effectiveness of the unit or the wellbeing and the welfare of my Marines.”)

I think that is the issue to be decided. You must ask yourself, then, “Should we permit this aberration of good sense, of logic and the good of the unit? Must we permit that in order to permit an extraordinarily few to become generals and admirals, as they would wish to be?”

I cannot comment to you accurately, or even with experience, on whether a woman would be an effective pilot in combat, never having been a pilot myself. I will tell you at the same time, having been shot down in a helicopter at Khe Sanh on two consecutive days, different aircraft, that no woman could have sustained the crash of the aircraft or the physical effort necessary after the crash to evacuate myself and another 16 dead and wounded in order to remove myself from this combat necessity. No woman could have done that.

No woman remaining alive after such an event would have had the physical power to extract those killed and wounded men; the pilots and the crew, absolutely no one. To see them effectively out of this enemy sanctuary, with no friendlies around me, while I remained behind, I don’t think any of them would have done that, would have been physically able to do that, and if in fact they had chosen to do that.

It took not only brute physical strength, pulling man after man out of the aircraft and into another, it took fighting back overwhelming psychological pressure to continue this grisly work, removing legs from the cockpit, parts of other bodies, and it took overwhelming—overwhelming—effort to overcome any human’s gut visceral instinct to get on that same aircraft, rather than stay behind, as the only person, while that aircraft full of casualties left; and I did so.

Now, I won’t tell you that women do not have courage. Every single mother has courage. I will not tell you that women do not have strength. Women have strength beyond description, and certainly strength of character. I will tell you, however, that this combination of strength, courage, and the suppression of emotion that is required on a daily, perhaps hourly, basis on the battlefield is rare indeed, rare in the species, and is not normally found in the female.

Now, does that offend you? I’m sorry. This is simply an observation. Can women fight? Yes, they can. Can they fight in the conditions of the battlefield of which I am familiar, and the cohesiveness of the unit, and can they add to that cohesiveness? I don’t think so. Should they do this? Hell, no! Never.

What is the purpose of it? Why should they? For the self aggrandizement of a few? Less than one-half of one percent who want to climb this ladder of promotion, is that a good reason, good enough to send our daughters, our sisters, our mothers off to the stinking filth of ground combat? And if you think so—and when I say “you,” I refer to the American public—if you think so, then you’re different from me. God knows, you’re different from me.

If you think women have a so-to-speak right to grovel in this filth, to live in it just because someone above them, senior to them, wants to be promoted, then, my God, what has happened to the American character and the classical idea, western idea, of womanhood?

And some would say, “Well, we’ll try this. We’ll try to do this. We’ll see if it works. We’ll experiment.” Well, if you do that, then a part of your experiment—no small part—will be the guaranteed, absolutely certain deaths of men and women in mixed-gender units simply because they are there. Thus, the men and women as units in which they are intermixed become completely ineffective on the battlefield, and in fact invite attack and destruction by the enemy, knowing that these are mixed-gender units.

Is it any surprise, as we knew would happen—all of us knew this—that a captured female in the Gulf War was raped, sodomized and violated by her captors? Does that come as a surprise to anyone?

Those that permitted this to happen, who sent her on that mission, should be themselves admonished, if not court-martialed, because that is the way the enemy sees women in combat; all of our enemies. And that is why they will treat—that is the way they will treat female captives or the female wounded left on the battlefield. That is precisely what will happen to them. We know that. We have seen the enemy (combat veterans).

I have seen the enemy, and I know what they do to Marines. They skin them alive—one of my compatriots at Con-Tien—nail them to trees. I’ve seen that, with bridging spikes.

None of this gets reported. None of this reaches the sanctity and the antiseptic cleanliness of a hearing room. It’s only on the battlefield. None of this is chosen to report. This is what happens on the battlefield. This is reality. The picture of a man’s privates cut off and stuffed in his mouth, or his fingers cut off so they can pull his rings off, and other unspeakable atrocities. I’ve seen this. No pictures are ever taken of that.

They are never shown. And if they are taken, no one is interested. But that’s a regular, not unusual, event in ground combat. That is regular.

Now, admittedly, this doesn’t happen in the cockpit. The cockpit is relatively clean. But it damn sure happens when the cockpit collides with the earth, is no longer airborne, and it is suddenly exposed to the enemy. We have seen that. We know that. We have already heard testimony to that.

A great majority of our wars are with enemies that come from societies where women are not valued as equals, and in many cases have no value whatsoever, other than the procreation of warriors. Is that a shocking fact or statement? Well, it shouldn’t be. Americans tend to look at other countries and other peoples with the naive statement that: “Oh, they’re just like us.” Well, they’re not just like us. They’re completely different from us, and we are seeing this more and more, particularly as our once greatest adversary (Russia) now reputedly is no longer so.

They have very little value for human life—why else would the Soviets have kept our own prisoners?—particularly on the battlefield, and they have almost zero value for females. Females are many times, if not mostly, seen as the pleasurable accompaniment, meant for the pleasure and the sustainment of the men who are actually doing the fighting. And that has taken place in our history, all of our lifetimes.

In a group of prisoners I captured near Khe Sanh, about a dozen enemy, one was a woman. We put them in a compound and we guarded them. They forced her apart, and then during the night—this is all North Vietnamese—they stripped her of absolutely everything, including the rations she was given. The next morning we found her without a stitch of clothing or any other possession, nearly frozen to death, and she was forced not to share in what little sustenance we had given all of the prisoners. They didn’t care about her. They cared about themselves.

If we see women as equals on the battlefield, you can be absolutely certain that the enemy do not see them as equals. They see them as victims. The minute a woman is captured, she is no longer a POW; she is a victim and an easy prey, and is someone upon which they can satisfy themselves and their desires. That is the generally accepted view that our enemy has of the so-called woman warrior.

Think back to the prisoners in the Philippines who were captured by the Japanese, which was referred to earlier today.

When that airplane, with its female pilot, returns to earth or collides with earth or she must bail out of it, she is no longer a female pilot; she is now a victim, and made so by the incredible stupidity of those who would permit her to encounter with the enemy. She is no longer protected by our own standards of decency, or the Geneva Convention, which few of our enemies have paid the least bit of attention to. She is no longer protected by the well-wishers and the hand-wringing and the pleas and the prayers of the folks here at home. She is a victim, and she will be treated accordingly.

We have just seen this, for God’s sake, in the Gulf War.

I have known many prisoners of war. Last year a Marine was to have been sent to me as my executive officer, who was a prisoner of war for not even two weeks in the Gulf War, he called me and said, “Colonel, I’m sorry to report that I simply cannot come to you as your executive officer, no matter how exciting or enjoyable this duty is. My mind is not right. I must be close to a hospital. I cannot deal with reality. I cannot accept the responsibility for the development of young officer candidates, or even for my own actions.” And that for less than a month in a POW camp with an enemy I dare say more tolerant than the enemy in North Vietnam.

I’ll take this uniform off in a week, a uniform which I have worn with great pride now, first issued to me 35 years ago, and that will be, for me, a sad day. However, nothing compares with the sadness that I and thousands of other Marines will feel knowing that the sure loss of combat effectiveness in our units will take place if women are introduced into them; profound sadness and equally profound shock. And all for the wrong reason. We don’t need them in our combat units. We don’t want them in our combat units. And they don’t want to be in our combat units. And, as I have said, they have told you this over and over, not this commission. They have said, “don’t put us in your combat units,” the exception being those self-serving few who would achieve higher rank in their own view.

People who do this do not respect women. They demean women. They would damn them to a hell that they themselves would never have to suffer, because the women who do this would be the junior enlisteds.

I’ll stop my comments there.

COMMISSIONER DONNELLY: Thank you, Colonel Ripley, for your very graphic testimony. We have heard several times in the last couple of days that when we have training regimens, that it is okay to have gender-norming, different standards for physical fitness, because there are physical differences between men and women.

And I know—well, the Naval Academy honors you with a display there. I didn’t see it, but I understand that there is, and you are one of the most famous graduates, and you know that, as at the other service academies, this idea of having dual standards is very much reality.

The question to you is, do you think that should continue—if the combat training is not done at the Naval Academy, I have been told, “When, it’s done somewhere else,” [sic] but is there a dissonance there? Should it not be continuous? Do you think it should be continuous, or do you think it is okay to have one kind of training regimen and dual standards for just combat support, and then a different set of standards for direct combat or combat MOSs?

COLONEL RIPLEY: I’ll preface my comments by saying that I am on one extreme, I think—it’s rather obvious—and that is I feel that the training for ground combat must be as intensive and as physically demanding as it can possibly be, which likens it to the reality of ground combat.

I think it would be impractical for the Naval Academy, or perhaps any other institution at the undergraduate or pre-specialty level, to have that same degree of demand, certainly the physical demand, if not the emotional demand, in all of its students.

I would also say that the changing of standards, the oft-used term “gender-norming,” is in fact a depreciation. You are reducing your standards. You’re not “norming” your standards; you’re lowering your standards. It’s a simple fact. If your standards were at one time, as was the case with Tom Draude and myself at the Naval Academy, to perform certain numbers of physical activities, push-ups, pull-ups, boxing, wrestling, the obstacle course, et cetera, et cetera, and then suddenly that changes, and it changes down, then you have lowered your standards. Call it what it is, you have lowered your standards.

Does that answer the question?

COMMISSIONER DONNELLY: Yes, it does, but do you think it is possible to have—you said it would be impractical at the Naval Academy to have a single standard. Is that what you mean?

COLONEL RIPLEY: I think it is impractical to have for combat training the same standards. However, I think that, failing that, there are still great requirements, certainly physical requirements, which males should be held to that females cannot be held to.

That does not mean that females, by their presence, should lower the overall standards for the group. I think it is okay—and I saw this—to have different standards for males and females, rather than this so-called norming process that West Point uses.

COMMISSIONER DONNELLY: Do you think that the standards, then, would be lowered if women were put into combat MOSs, or the attempt was made to have them?

COLONEL RIPLEY: There can’t be any question of that.

COMMISSIONER DONNELLY: No question of that?

COLONEL RIPLEY: I think the fact is that you must know. I’ll give you an example. We found out when we were told to put women in drill teams—I think this was during the Ford or the Carter Administration; I can’t remember which—that we had to remove the operating rod springs in our weapons because women could not come to inspection of arms. They couldn’t. The spring has a nine-pound release, and they couldn’t move the rifle bolt to the rear.

There are simple physical, psychological, physiological differences that would require this different standard.

Do I feel, if I infer from your question, that this is correct? No, I don’t. There are certain limitations on weapons and weapons systems that are essential; that cannot be changed. You reduce the operating rod spring, you make a weapon lighter—the M-16 is a perfect example—it becomes ineffective. We couldn’t use the bayonet on the M-16 because the barrel was so light it would bend the barrel. We have corrected that in the Marine Corps. We now have a much heavier barrel, and we increased the buffer spring tension.

A woman cannot pull the cocking handle on a 50-caliber machine gun. She cannot feed a round into the weapon. They cannot undo a hatch, as a man can; the closure grip on a simple hatch. That’s a tank hatch or a hatch in a submarine. It can’t be done without assistance. Should that be changed? Personally, I don’t think so. I think these were designed with the ergonomics and the human application at some point, considerably earlier, and we found these weapons systems to work perfectly. They are certainly rugged, and they should be.

Weapons of today are nowhere near the ruggedness of the M-1 Garand, just by way of example. That’s not to say they are not good weapons, but they are designed with this ruggedness as a factor and, as such, they are more effective. If it is necessary to change it, I think we have derogated the overall effectiveness of the weapon.

COMMSSIONER MOSKOS: Thank you very much. Colonel Ripley, it was very fascinating about your story and testimony, in addition to the details, the graphic details.

We’ve been getting mixed signals, you know, from Marine Corps representatives on this question. I wondered if you wanted to comment on that. And my final remark, tying in with that one, is would you draw—where would you draw the lines in the Marines on women’s roles, period?

COLONEL RIPLEY: My first answer, sir, is I’ve got nothing to lose. And that isn’t meant to sound the least bit derogatory to those who perhaps do have something to lose. I have spoken very candidly my whole life, and this is an issue too important to hide behind personal concerns. It’s just too important.

And I’m not sure who gave you mixed signals, but I feel deep in my heart that anyone who has shared the experiences that I have—and I certainly am not the only one to have done that—feels virtually the same way I do; I can guarantee that—who has had ground combat at the company level for over two years.

Where I would draw the line? I would draw the line at any unit which is required by the mission and the nature of that unit to close with and to kill the enemy by close combat. That includes, in the Marine Corps, rough guess, about 75 percent of all of our combat Marines, all our Marines, and perhaps units; however you define that.

I would say nothing in a Marine division at the regimental level, or those units which are supporting those regiments, the infantry and the artillery regiment.

I would say nothing in combat support units which may find themselves in enemy areas, and that includes, by the way, truck drivers who happen to be carrying essentials from place to place.

(6:10 p.m.)

COLONEL RIPLEY (Continuing): In one particular ambush on the 21st of September—correction, 7th of September, many years ago, we had a 100 percent ambush, and the drivers were pulled out of their trucks and were flayed, if you know that term, and they were pinned to their vehicles and left to be there in agony as we closed to try to rescue them.

Combat is combat. Maybe I should begin with my definition of combat, which seems to be a widely diverging definition. Combat suggests combat, to com-bat (verb) someone.

It is an overt, aggressive act. It is not passively awaiting something to happen in a risk environment.

Exposure to combat is not combat. If it were, then we could define a garbage man as someone who performs in combat. Last year I think over 300 garbage men were lost as they fell off their trucks or got compacted in the trash. That’s twice the number that we lost in the Gulf War!

So exposure to combat is not combat, not at the infantry level. Combat suggests aggressive, violent behavior—violent behavior—and the satisfaction, the enjoyment that derives from this behavior, that is an essential part of combat, at least among Marines.

Take, for example, linebackers. Linebackers love to crunch somebody. They get a big kick out of knocking not the player down, but anyone down. There is a satisfaction derived from this sort of aggressive behavior. It is common in males. I’m not saying 100 percent, but it is common. And someone can probably define that by chemical balances, testosterone and all the other things. I’m not sure what causes it, but I can tell you it is common. And if it isn’t common, this man will never be a good Marine. We don’t want him.

Combat suggests this type of aggressive, violent behavior which begets some degree of satisfaction from having encountered and crushed the enemy, a good feeling, a feeling of victory, a wash of emotion. There is something good about this.

I do not subscribe to this feeling that we hate to fight, we don’t like to fight, somebody’s got to do it. We did it, and we enjoyed it. That did not mean that we would like to be there or that we were warmongers or we necessarily promoted the fact that we were there. We sure as hell didn’t. But we got an enormous amount of pleasure out of taking the fight to the enemy and ruining him in the process. That is combat.

It is not exposure to risk. If it were, then call it “risk.” Don’t call it combat. It’s a totally different thing. We put it under the amalgam, this generic term of combat, sitting in a barracks somewhere which is hit by a rocket, and we call that “combat.” That’s not combat. Combat is an aggressive act, the operative term. You must go after the enemy, you must go for his jugular, and you must enjoy doing it, at least to the point of requiring you to do it again without deriving some emotional hangup therefrom.

I’m sorry, sir, I forgot the rest of your question.

COMMISSIONER O’BEIRNE: Thank you. Colonel Ripley, I would like to ask you a general question about unit cohesion, which we have been discussing quite a bit here at the Commission. We have had at least some fighter pilots, for example, express some hesitation about flying with women making the—expressing the concern that they would be unable to treat a woman comrade the same as they could a male comrade, and we have had infantry, males in the infantry, express the same hesitation.

Based on your experience in supervising the training of these young men—on the other hand, we have been told that they could be trained out of that attitude, that if they trained enough together as either fighter pilots or as infantry troops, they would come to see one another as comrades and, over time, would not treat—males would not find themselves treating females any differently.

Based on your respective lengthy experience, do you think young men, either pilots or infantry troops, could over time be trained to treat female comrades the same as males?

COLONEL RIPLEY: I would say to you yes, absolutely yes, the fact that the females would be in a ground combat unit, infantry battalion, the men would, without question, resent it, it would destroy cohesion, wreck the unit. It would in fact set up not just a dual standard but a grossly unfair standard, because males already accommodate females. They accommodate the fact that females must have certain differences. They must have separate and better, by the nature of them, quarters. The quarters for females are private. They have better head facilities. They have better—just many better things, separate messing facilities in the desert, separate—a lot of things. We accommodate that. We don’t necessarily dislike it, but we understand why it is necessary.

If you did that in an infantry battalion, which must, of nature, reduce itself to the lowest denominator, meaning all personnel in that battalion, officer, enlisted, staff noncommissioned officer—everyone has to do the same thing. You dig your own hole, you fetch your own chow, you deal with your own personal hygiene, you: accommodate or you take whatever—share whatever lack of resources there happen to be, they would resent the fact, over a period of time, that the females must have their portion of water or whatever. And it would take a very short period of time that this accommodation which we now do would wear very thin, and it would turn to resentment, gross resentment.

I could give examples of that.

And I would also say that the mere fact that females would be in this unit would not, so to speak, equalize certain actions. The females would never carry the radios. The females would never be sent alone on an LP at night, the most unloved job in the whole unit. The females would never be required to do the things that the males are required to do, of nature, and expected.

No female would ever walk the point; simply would not. I dare say the men would not—would feel very uncomfortable with a female on point.

No female would be required in an emergency situation to move and get another couple of cans of link (machine gun ammunition) or more grenades.

No female would ever carry the outer ring of the base plate, which we don’t even have anymore.

No female would be expected to run a landline between your unit and an outpost.

No female would be required to carry “Peter and the Wolf,” a dead Marine, which only two male Marines can do, slung on a pole, because that’s the only way you can carry them in the jungle.

No female would be required to do 90 percent of the things with which I am familiar, simply because, in many cases, men would not stand for it. They would never, never permit a woman to do the things that they do, of nature, disliking, but they know they must do it.

I can tell you that unit cohesion would be destroyed.

COMMISSIONER WHITE: [Yes, the first question is for both of you to respond to, and then I have a follow-up question for Colonel Ripley.]

We have been told that part of the reason we need to seriously consider the further integration of women into the military, into combat positions, is because we need the best that there is, and that we can’t afford to overlook a segment of the population that may have skills that would be helpful to complete the military’s mission. I would like to know if you think that the current operational effectiveness of your particular branch of the service is lacking because we have not reviewed the active-duty women that are willing or desire those positions? Are we operating at decreased effectiveness?

COLONEL RIPLEY: I’ll answer first by—I’d like to address this to perhaps those who haven’t read my statement on women in ground combat. The issue of American females in combat should first be approached from the standpoint of need, simple need. Using the Vietnam War as a model, we can use the following analysis—and this, by the way, draws on figures from the Veterans Administration—8.7 million men served on active duty during the Vietnam era, 8.7 million, and that was from March ‘64 to January ‘73.

Now, of that 8.7 million, 3.4 million served in the Southeast Asia theater, which consisted of the surrounding countries of Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, as well as, of course, the water and the air space surrounding them. By the way, that is only eight percent—that 3.4 million is only eight percent of all men eligible for the draft during that time—eight percent. Ninety-two percent of the men eligible for the draft were doing something else.

Now, 2.6 million of the 3.4 million who could consider themselves Vietnam veterans, just having been some place in Southeast Asia—2.6 million served in Vietnam, that is, under the threat of enemy action—in the country—2.6 million.

As you can see, I am rapidly going down. Only one in five—one in five of the 2.6 million—fought in combat in a ground combat role, perhaps a half a million, less than a million, a half a million, and two in five provided close combat support, either frequent or infrequent; roughly one million.

Now, I can also tell you that a good figure of 30 percent of those, of that half a million, really never fought in combat, certainly not sustained combat. And I will postulate that that number, the 30 percent, they never saw it because the nature of war is such that squads, platoons and companies did an overwhelming majority of the fighting, whereas the combat support and the combat service support personnel were essentially confined to fire bases which supported those ground combat units, the squads, the platoons, the companies.

The exceptions were in the large-unit actions later in the war, after 1966, late ‘66, along the DMZ, and the hazardous movement, the very hazardous movement, going between combat bases for resupply and so forth, subject to enemy action.

So we can finally conclude that, at most, there were 350,000 men who saw ground combat on a regular basis in Vietnam, from my original figure of 8.7 million, 3.4 million, and 2.6 million.

The need, therefore, for women to serve in ground combat in any unit, or to augment those units, does not exist. We are not losing a very exceedingly valuable asset by not having women in our combat units.

COMMISSIONER WHITE: I would like to ask two other questions. Colonel Ripley, you had mentioned earlier that you don’t have anything to lose in discussing this issue. Was that just for yourself, or have you heard talk, or are you aware of other people that are concerned or might have reservations about expressing their gut reactions to this issue?

COLONEL RIPLEY: I’ve heard nothing whatsoever. These are my personal opinions. I’m on a very remote outpost. I rarely get to see my friends in the Marine Corps. I should turn that statement around and say I have a lot to gain, too, rather than nothing to lose. I have an awful lot to gain by, as I stated earlier, protecting American womanhood, if that is not too gratuitous a statement.

COMMISSIONER WHITE: If I could direct one more question at Colonel Ripley, you are a graduate of the Naval Academy, and I visited there in late April and discovered that they seem to be on a mission now of, as they put it, dispelling the “myth” that their mission is to train men to lead other men in combat, or to train warriors, that it has broadened into kind of training the whole person, and one person even said that we shouldn’t even be thinking so much about training for war but that we should be thinking more about peace and so forth, and that they are trying to get away from the so-called myth.

I wonder, have you observed any changes in the style of teaching or the attitudes promoted there, or the manner of instruction since your days at the Naval Academy?

COLONEL RIPLEY: I left the Naval Academy five years ago as the senior Marine. At that time, I was living under the same myth, and this so-called myth was up until that time, for 30-some years of my association with the Naval Academy, beginning as a midshipmen, it was a well-understood fact, and it was stated as such, certainly in the statements, the policy statements by the Academy, right up until my service there,

leaving in 1987, and certainly that was engendered and spoken publicly by innumerable guest speakers that came to the Naval Academy.

It was only when I read in The Navy Times, I think about a year-and-a-half ago, before the present Superintendent’s arrival, that the previous Superintendent did not want any more guest speakers to talk about combat—experiences in combat—did not value the experiences themselves, and thought they were not necessarily productive for young midshipmen, and gave the wrong opinion; gave the wrong attitude. It was demeaning for those who would not end up in combat. That’s the first I had ever heard of that.

The various things we did there to train, (when I was a midshipman) to instill this aggressive behavior I referred to earlier, they (this new Superintendent) questioned whether that was important anymore. The running of the O-course, (obstacle course) for example, became “irrelevant.” It was no longer “relevant” to run the O-course. It was no longer relevant to have boxing and wrestling, aggressive type sports, contact sports.

A wag, a friend of mine, said, “Well, if that is the case, why don’t we just do away with football? Maybe that is too aggressive!” And although that is not meant to be necessarily humorous, it does bear certain introspection. Why not do away with anything whatsoever that suggests aggressive—aggression or aggressive behavior? So the issue of whether the Academy exists, or any academies exist, to train so-called warriors or those prepared for their ultimate duty in a combat environment, that issue, to me, should never even be voiced. Obviously, we have an academy to train these warriors, and those with the expectation of combat and service in a combat environment, in whatever capacity, service support or combat support—obviously.

And if that is not the case, then one must ask the obvious question: Why have an academy?

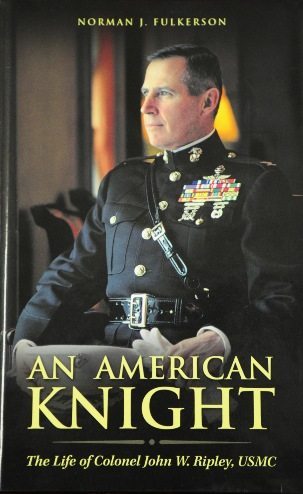

Read more about the life of Colonel Ripley in the book An American Knight: The Life of John W. Ripley, USMC.